In my previous post I made the perhaps rather startling claim that, in the long run, infinite growth can be considered to be in some sense equivalent to zero growth. This is a claim that deserves some more explanation both because it is possibly contentious and because it is extremely important to the grand scheme of the theory I am developing in this series of posts.

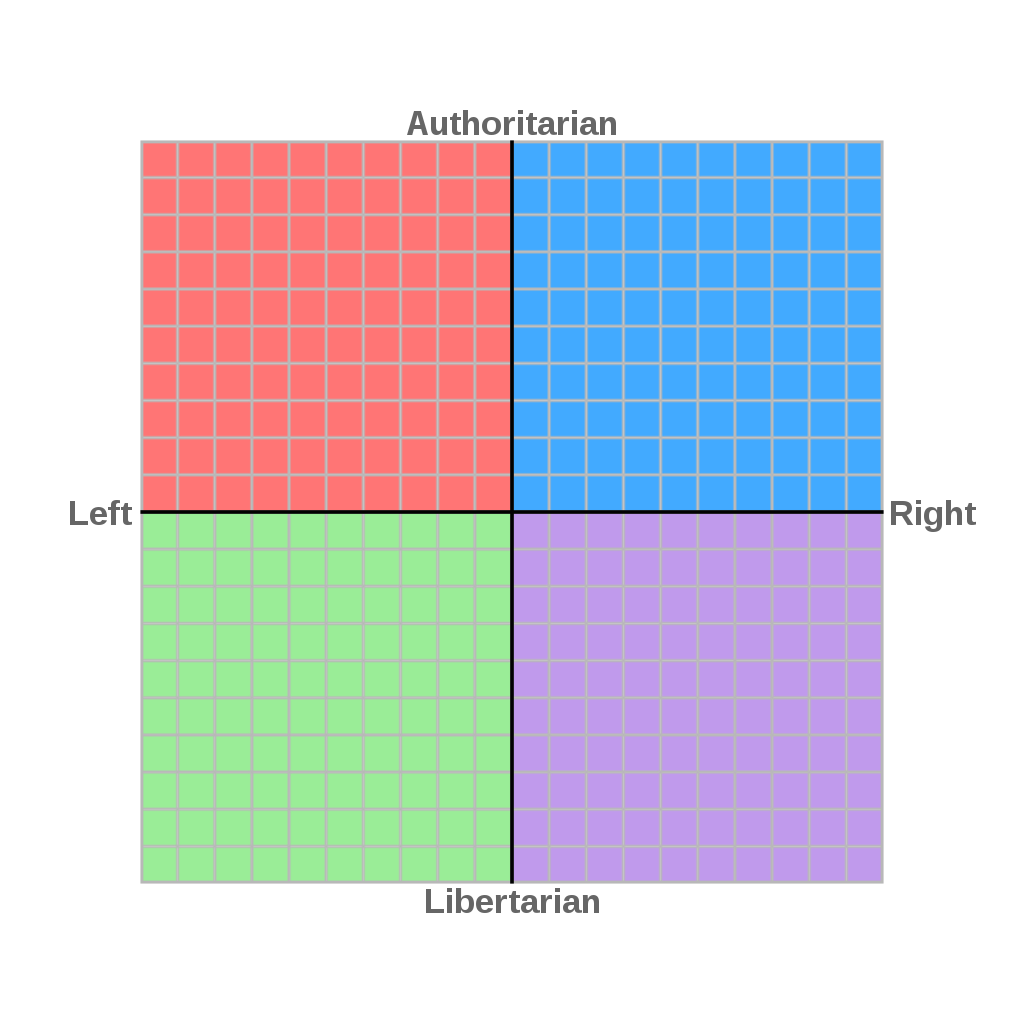

To help understand this point of view I would like to call on two completely separate ideas. One is the horseshoe theory of the political compass, and the other is the substitution of Zipf’s law for Shannon entropy as an information theoretic measure in certain contexts. In this post I will explain the first of these: Horseshoe theory.

The political compass is a useful way of expanding the simplistic left-wing, right-wing dichotomy into something more useful. The left-right politics dates back to post-revolution France and can broadly be understood as either a progressive-conservative, socialist-mercantilist, or revolutionary-establishment axis.

It is perhaps more intuitive to understand the libertarian-authoritarian axis. As the names suggests, authoritarians believe that the common weal is best served by a centralization of power. The nanny state, in other words. There are some good reasons to believe that this may be partly true, due to problems such as the tragedy of the commons—where no one has an interest in maintaining shared property—or the public goods dilemma—where the interests of every individual in a group can conflict with the interests of the group as a whole.

A good, if artificial, example of this may be where everybody in the neighborhood wants to make noise one (and only one) day of the week and want quiet for the remainder. If everybody prefers a different day to make noise, everybody will be unhappy. So it makes sense to give up the private preference for which day to make noise in return for the public good of everybody getting to make noise on one day. Notice, though, that there may be some people who preferred the chosen day to begin with. It is usually impossible to avoid such unfair benefits (or costs) from public solutions entirely.

The video below gives a good description of the public good dilemma (but, for the record, I disagree with the theory of taxation it provides. But that’s for later…)

On the other end of the spectrum is the libertarian ideal, where individuals are ends in themselves and not means to an end. This, too, has a solid theoretical foundation as a way to organize a society. After all, birds flock without the need for centralized government.

Order emerges spontaneously from sufficiently many, sufficiently complex interactions.

From an economic perspective, this idea is captured by the Nash equilibrium, of “A Beautiful Mind” fame. Here, players in a game, such as people participating in a free economy, will naturally tend towards equilibria where they cannot improve their position. What’s more, because economists separate the idea of utility from monetary value, it is entirely possible for a collection of individuals to act in a way that maximizes collective utility (call it “happiness” for the sake of argument) even if tangible (say “monetary”) outcomes vary greatly.

What’s more, since utility is almost impossible to directly measure, while money is inherently measurable (in principle, at least), it is much more likely that a central authority disturbs such a maximal utility arrangement than that it enhances it.

Obviously, the authoritarian-libertarian axis is not so clear-cut as some would have one believe.

Full disclosure here: My own position on the compass is what is known as moderate lib-center, so about halfway down the vertical axis (tending towards libertarianism) and in the middle of the horizontal one (neither left nor right-wing). So, to some extent, my political views are an embodiment of the moderation I am arguing for.

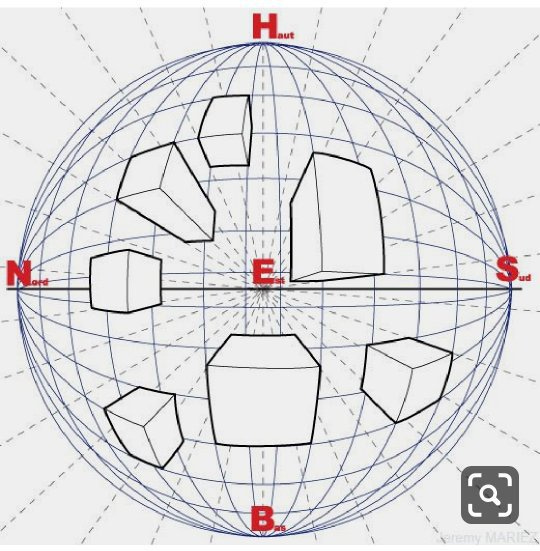

Now, to the point of this post. There are many ways to enhance and extend the political compass, but one of my favorites is horseshoe theory, in terms of which the edges of the compass are connected, so that surface is a sphere rather than a flat square sheet.

To see how this may work consider the revolutionary who achieves power. If we accept the progressive-conservative interpretation of left-right, then the revolutionary becomes the establishment. A good example of this is the debate about the legality of abortion in terms of Roe vs. Wade. Independently of whether they are “pro-life” or “pro-choice”, many critics have grave concerns with the U.S. Supreme Court decision or purely technical grounds. But let’s accept it here as established law regardless. So the question is: Are people who accept this law really progressive? Are the people who want to overturn it really conservative? When one reaches the extremes of either point of view, the idea of classifying things in this way becomes more and more absurd. In the end, the real conflict on the left-right spectrum is between people who weigh the issues (centrist) and those who are dogmatic about them, regardless of whether they see themselves as establishment or not.

Today’s radical idea is tomorrow’s pledge of allegiance.

Similarly, with the authoritarian-libertarian axis, the distinction breaks down when one allows different levels of analysis to emerge. If one allows oneself the luxury of thinking of government as a benevolent, thinking entity, then it can very much solve the public goods dilemma and provide an environment where a Nash equilibrium that maximizes private benefit for all can spontaneously emerge without intervention.

However, if one deigns to recall that government is staffed by individuals who can (and will) influence public decisions to benefit their tribe—if not themselves directly—then it becomes clear that an authoritarian is really nothing more than a libertarian for people in power. So the paradox emerges that in order to best serve the public good, government authority must be at once minimized so that people in power serve only the public, and maximized so that they can overturn the will of individuals where needed.

Once again, the conflict lies not between the two opposing poles, but between the center, which believes things should be evaluated independently of its relationship to government authority on a case by case basis and those who think that either absolute control or lack thereof are the ideal. My own tendencies to veer towards the libertarian end of the spectrum stems from my sincere belief in the power of spontaneous self organization, but even I can recognize that there are times when this not enough to ensure an optimal society for all.

So this, basically, is my interpretation of horseshoe theory. More of a sphere with vanishing points of disagreement at the extremes than a horseshoe proper, in my opinion. Notice too, incidentally, that this perspective collapse the opposing axis at the extreme. So at the extreme, authoritarianism or libertarianism collapses left-right distinctions, and mutatis mutandis for extreme right or left wings.

The key point that I would like to make about this is that many seemingly intractable problems are really conflicts between levels of analysis and between orders of abstraction, rather than things themselves. It is my contention that:

Most problems have an ideal level of abstraction which resolves conflicts of analysis.

I saw a comment you made on Rounding The Earth Substack, so eloquently written, I wanted to comment, but thought it more appropriate on your own Substack instead. I love reading things written by crazy-intelligent people, even if I don’t understand all or even much of it because it challenges and expands my brain. Very thought provoking. My belief is that we are here on this earth to expand our consciousness, which is done though reading ideas such as the ones you share. (By crazy intelligent I mean that in a good way)